For many Christians, one of the most difficult aspects of Tolkien’s stories, similar to (if less obvious than) the Harry Potter stories of J.K. Rowling, is their use of “magic.” Indeed, some even go so far as to compare the wizards and witches in Rowling’s world to Tolkien’s Elves and Istari, and fans will often ask whether Dumbledore or Gandalf would win in a magic duel. For this reason, some Christian parents have not only seen Harry Potter as inappropriate for their children to read, with concerns that it could lead them to practice Wiccan-type pagan magic on their own and potentially open themselves to demonic influences, but have even accused Tolkien’s stories of similar faults and dangers. It is not the purpose of this article to deal with the question of Harry Potter but with Tolkien, according to his own Catholic perspective.

Some of Tolkien’s views on magic and mythology were personal to him, based on his beliefs as a Catholic, while others are explicitly rooted in Catholic tradition. The Church has always taught, of course, that “magic,” used in the occultic sense, is intrinsically evil. (See CCC 2115-2117) As a Catholic, Tolkien shared this faith, and the use of “magic” as described in this passage of the Catechism is reflected in the sorcery practiced by certain evil characters in his stories, such as the Witch-king, whose unnatural power derives from Sauron and thus constitutes “recourse to Satan or demons”, as the Catechism describes. It should also be made clear that Tolkien does not distinguish this demonic sorcery for what is often called “good” or “white” magic: there is no good magic in Tolkien’s world precisely because there is no good magic in the primary world, as he well knew.

But, one might ask, isn’t the power used by the Istari and the Elves just “good” magic? Celebrimbor the Elf even helped make the Rings of Power, worn by Men, Elves and Dwarves, which would become subject to the One Ring of Sauron, who learned ring-making from and with Celebrimbor. And aren’t the staffs of the Five Wizards the same as wands in Harry Potter? Tolkien even used the term “wand” for Gandalf’s staff three times in The Hobbit.[1] This is why Gandalf made sure to keep his staff in order to free Théoden from being ensorcelled by Gríma Wormtongue – right?

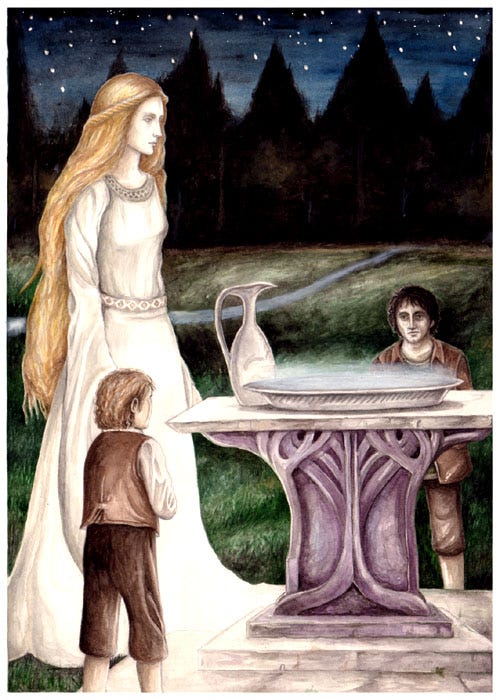

Tolkien himself admitted that “I have not used ‘magic’ consistently, and indeed the Elven-queen Galadriel is obliged to remonstrate with the Hobbits on their confused use of the word both for the devices and operations of the Enemy, and for those of the Elves.” The remonstration he mentions is important for distinguishing between the sorcery of the Enemy and the “magic” of the Elves and Istari. Galadriel said (in reference to her Mirror):

‘For this is what your folk would call magic, I believe; though I do not understand clearly what they mean; and they seem to use the same word of the deceits of the Enemy. But this, if you will, is the magic of Galadriel. Did you not say that you wished to see Elf-magic?’[2]

In the letter quoted above, Tolkien goes on to explain that “[Elf] ‘magic’ is Art, delivered from many of its human limitations: more effortless, more quick, more complete (product, and vision in unflawed correspondence). And its object is Art not Power, sub-creation not domination and tyrannous re-forming of Creation.” The Elves, he says, are “the representatives of sub-creation par excellence” and their Fall, unlike that of Men, pertained to this Art, to a possessiveness of their works by which, “clinging to the things made as ‘its own’, the sub-creator wishes to be the Lord and God of his private creation.” As Gandalf once warned Frodo,[3] for mortals this temptation is especially dangerous, since, as Tolkien explained, it can lead them to “rebel against the laws of the Creator – especially against mortality.”

In this same letter, Tolkien clearly described his views on the magic which is condemned by the Church:

Both of these [Fall and Mortality] (alone or together) will lead to the desire for Power, for making the will more quickly effective, – and so to the Machine (or Magic). By the last I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents – or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills. The Machine is our more obvious modern form though more closely related to Magic than is usually recognised.

Magic, as Tolkien wrote in On Fairy-Stories, is wholly different from the subcreative art of the Elves – what in that essay he called Enchantment: “Enchantment produces a Secondary World into which both designer and spectator can enter, to the satisfaction of their senses while they are inside; but in its purity it is artistic in desire and purpose. Magic produces, or pretends to produce, an alteration in the Primary World. It does not matter by whom it is said to be practised, fay or mortal, it remains distinct from the other two; it is not an art but a technique; its desire is power in this world, domination of things and wills.”[4] In other words, magic is the attempt, through means both supernatural and natural, to coerce and dominate – whether the material world or other human wills – in violation of God’s law, whereas enchantment is art done in imitation of God the Creator, in cooperation with His law and for purposes of reciprocal delight and edification, not power. In this way, magic and machines are not fundamentally different, and the same spirit of coercion need not even make use of an “apparatus” as he calls it – they can also involve the misuse of “inherent inner powers or talents… with the corrupted motive of dominating”.[5]

While Tolkien does not distinguish between good and bad magic, in letter 155 he does use an old distinction between what he calls “magia” and “goeteia.” The first is the power to manipulate the physical, external world, while the latter is the ability to influence subjective wills. He explains that, in Middle-earth, either can be used for good or bad, depending on the intention of the user, but that such power is not intrinsic to Men – the only Men who can use “magic” are either sorcerers given unnatural power by demonic entities (Morgoth, Sauron), or who have elvish ancestry, such as Aragorn and the Dúnedain. For evil sorcerers, “magia [is used] to bulldoze both people and things, and [their] goeteia to terrify and subjugate.”

For Elves and Istari, however, magia, which they use “sparingly”, produces “real results (like fire in a wet faggot) for specific beneficent purposes. Their goetic effects are entirely artistic and not intended to deceive: they never deceive Elves (but may deceive or bewilder unaware Men) since the difference is to them as clear as the difference to us between fiction, painting, and sculpture, and ‘life’.” The difference, he says, is that the motive of villains is to dominate, while good people who possess this power innately use it benevolently. The magic condemned by the Church, however, is only that which is unnatural to man and involves domination; this occultism is fundamentally distinct from the art of the Elves or the authority of wizards. It is closer to human artistry or even to technology used in an improper way, as the same good or bad motives can also be applied to these more “natural” powers. For either magic or machines and for the sake of “immediacy,” one may “lose sight of objects, become cruel, and like smashing, hurting, and defiling as such.” This tyranny is possible even without occultism.

Elves, in Tolkien’s stories, “represent, as it were, the artistic, aesthetic, and purely scientific aspects of the Humane nature raised to a higher level than is actually seen in Men. That is: they have a devoted love of the physical world, and a desire to observe and understand it for its own sake and as ‘other’ – sc. as a reality derived from God in the same degree as themselves – not as a material for use or as a power-platform. They also possess a ‘subcreational’ or artistic faculty of great excellence.”[6] If the rope and cloaks of the Elves of Lothlorien can be said to be “magical,” it is only in this artistic sense, because Elves “put the thought of all that we love into all that we make”[7] – they are not like the magical objects used by Harry Potter. They are not devices or charms placed onto something; rather, they are expressions of the Elves’ natural artistry, with the same beauty and enchantment as artefacts of human art in the primary world.

The Istari of Middle-earth are often called “wizards” by Men. Tolkien used this term as a translation (“perhaps not suitable”)[8] “because of the connexion of ‘wizard’ with wise and so with ‘witting’ and knowing.” (The use of “wand,” and for that matter of “elf,” is also a mannish phrase for things unfamiliar to them – and to us.) A modern form of this use of “wizard” would be “wizened,” which has no connotation of magic but only of wisdom. In truth, “[Gandalf] is not, of course, a human being (Man or Hobbit). There are naturally no precise modern terms to say what he was. I wd. venture to say that he was an incarnate ‘angel’ – strictly an ἄγγελος: that is, with the other Istari, wizards, ‘those who know’, an emissary from the Lords of the West, sent to Middle-earth, as the great crisis of Sauron loomed on the horizon… They are actually emissaries from the True West, and so mediately from God, sent precisely to strengthen the resistance of the ‘good’, when the Valar become aware that the shadow of Sauron is taking shape again.”[9]

Accordingly, the “magic” used by the Istari is not pagan, nor is it even elvish; rather, the Istari as angels have special power over Creation and authority from God, symbolized by their crozier-like staffs. For demons like Morgoth and Sauron, this power has become corrupted into sorcery, which they can share with their minions, just like demons in the primary world. What Tolkien sometimes calls “spells” reflects the power of words which he recognized (as in the word “Gospel,” God-spell), as well as the sacramental nature of his world, where the spiritual is communicated through the material, for good or ill.

As Tolkien made clear, there is more in common between demonic sorcery and modern machine-guns and bombs than with the artistic enchantment of the Elves or the angelic power of the Istari. For this reason, it is inappropriate to compare Tolkien’s use of magic to Rowling’s, who makes no similar distinctions, and parents should feel secure in allowing their children to read and enjoy the Catholic tales of Middle-earth.

(Cover image source: “Nazgûl at the Walls,” by Ted Nasmith: https://tolkiengateway.net/w/index.php?curid=8440)

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (Mariner Books, 2012), 65, 67, 107. Kindle.

[2] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (Mariner Books, 2004), 361. Kindle.

[3] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 46-47.

[4] J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” at University of Houston, at https://uh.edu.

[5] J.R.R. Tolkien; Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien (eds), The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (London: HarperCollins, 2012), letter 131. Kindle.

[6] Tolkien, Letter 181.

[7] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 370.

[8] Tolkien, Letter 144.

[9] Tolkien, Letter 156.

Kaleb- This is an interesting breakdown on magic as it relates to classic literature. Glad I found it. Thanks for sharing.

Great essay on the particulars of sorcery in Tolkien's world, love it!