One of if not the best adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s subcreated world is The Lord of the Rings Online. It combines an exact adherence to the descriptions, storylines and characterizations in Tolkien’s works with original stories that are surprisingly faithful to the material while filling in regions and backstories that Tolkien did not have time to explore fully. I have been playing the MMORPG, which is now free-to-play, with my father for many years and it has allowed us to enjoy Tolkien’s incredible world in a uniquely immersive and cooperative way.

I mention this great video game, which I highly recommend, because it has an element to it that, for people unfamiliar with Tolkien’s legendarium or even for many who know them well, could seem perplexing. One of the classes you can pick from when making a new character, which determines his abilities and influences the overall experience of the game, is called Minstrel. While most of the classes in the game use powers that are more familiar, such as Hunters using archery, Champions using melee weapons and even Lore-Masters using semi-magical effects and a staff like Gandalf, Minstrels are unique in that their power comes from music. By singing at allies or enemies, using a wide range of instruments and even employing hymns to the Valar or the Five Wizards, Minstrels can heal and embolden their friends or damage and even kill enemies without ever hitting them with a traditional or magical power. Watching a Minstrel character kill a massive Uruk-hai by strumming a theorbo, whistling a flute or performing a song can seem almost comical compared to the more “realistic” attacks of other classes.

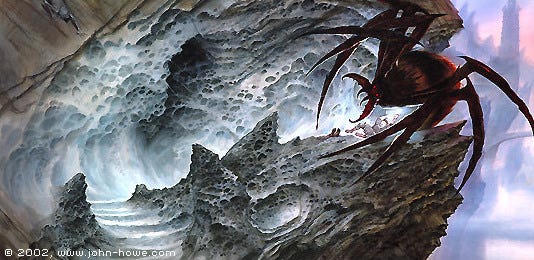

In truth, however, the Minstrel’s power of music should not be surprising for a true Tolkien fan. Throughout his stories, especially The Lord of the Rings but also in The Hobbit and The Silmarillion, as well as the other unfinished tales compiled by Christopher Tolkien, music is not only for inspiration or entertainment but has a real capacity to combat the forces of evil which can be even more effective than ordinary weapons. Quoting the song of the Elves of Gildor Inglorion, Frodo cries out “O Elbereth! Gilthoniel!” while stabbing the foot of the Witch-King on Weathertop, and later Aragorn remarks, “More deadly to him was the name of Elbereth.”[1] Later, Sam will invoke the same prayer to the angelic Vala while fighting Shelob, the memory of Gildor’s song in the Shire and “the music of the Elves as it came through his sleep in the Hall of Fire in the house of Elrond” reminding him of Galadriel and her Phial, which fills with heavenly light at his song and repels the demonic spider. The same words are then used to quell the Watchers so that Sam and Frodo can pass out of the Tower of Cirith Ungol.[2]

There are many other instances like this in Tolkien’s mythopoeic stories. Horns are especially powerful in Middle-earth. The Great Horn trumpeted by Boromir has the power to terrify the goblins of Moria and even briefly halt the demon Balrog while later calling the Fellowship to him as he defended Merry and Pippin from the Uruk-hai who were briefly stunned by its clarion call, and with the blast of the horn of Helm Hammerhand at Helm’s Deep, “the Orcs cast themselves on their faces and covered their ears with their claws” as Théoden led the eucatastrophic charge which would soon be joined by the saving forces of Gandalf, Erkenbrand and the Huorns of Fangorn.[3] And of course, most powerfully of all, the enigmatic Tom Bombadil’s only evident power is song, which he uses to calm Old Man Willow and to free the Hobbits from the corruption of the Barrow-Wights, called by Frodo’s recitation of the song Tom had taught them to sing if ever they were in need.[4] In a sense, Tom continues the legacy of the Elf princess Lúthien Tinúviel, who in The Silmarillion had such a powerful voice that her song could blind and stupefy Morgoth himself.[5]

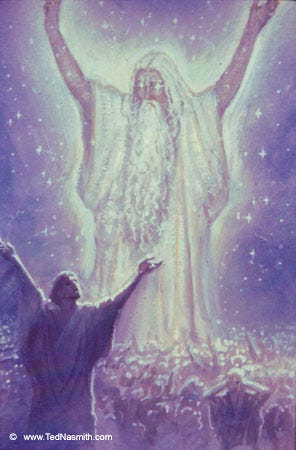

Perhaps the most mystical and revealing use of song, however, in all of Tolkien’s stories is in the Ainulindalë, the Creation narrative at the beginning of The Silmarillion. In this elvish version of Genesis, God, here named Eru Ilúvatar, creates angelic spirits called the Ainur, some of whom would later take on physical forms and be known as the Valar and Maiar, and teaches them music. With this power, they at first sing alone, then in harmony through the Great Music by which their thoughts are communicated through the power of the Holy Spirit, who is called the Flame Imperishable, in order to “adorn” subcreatively the theme begun by Ilúvatar. Like the Ainur themselves, the Music of the Ainur was “the offspring of his thought,” but Melkor (Morgoth), who is Tolkien’s subcreated version of Lucifer, introduced discord into the music and thus rebelled against God. Ilúvatar then used this music as the blueprint for the material world when He brought it into existence, incorporating the fallenness instigated by Melkor to work greater good and introducing many elements, both at the beginning and over time, that the Ainur did not know, and it is prophesied that, at the End, the Ainur and the Children of Ilúvatar will sing a song together in the eschatology of history.[6] In this way, music in Tolkien’s world not only has direct causative power over material beings and the ability to fight evil but is at the very root of Creation itself and is the first gift given by God to the angels.

But where does this view of music come from? Is it original to Tolkien? In fact, Tolkien’s belief in the power of music is firmly rooted in Scripture. Music is central to the liturgical celebrations of the Old Covenant (e.g. Lev 23:24; 1 Chron 13:8; 2 Chron 7:6) and directly inspired God to fill the Temple of Solomon with His glory-cloud. (2 Chron 5:13-14) Like horns in Middle-earth, trumpets are especially favored in Scripture. The trumpets and shouts of the Israelites processing before the Ark of the Covenant cause the walls of Jericho to fall down, as God promised; (Jos 6:4-5, 20) the foes of the Maccabees before the sound of their “holy trumpets… were put to flight: and there fell many of them wounded, and the rest fled into the strong hold”; (1 Mac 16:8) and angels usher in the Second Coming of Christ and the Last Judgment with trumpets. (Rev 8-9, 10:7, 11:15) This is only a few of the many examples of the power of music, both for the praise of God and the salvation of His people, which are replete in the Bible. Doubtless, as a devout Catholic who was intimately familiar with Scripture (in many languages, including the originals), Tolkien would have been inspired by this sacramental understanding of music which was common both to the Hebrews and to many peoples of the ancient world.

So, if you someday decide to try out The Lord of the Rings Online and feel drawn to make your new character a Minstrel, maybe their unique power will not now seem so strange.

(Cover image source: By Matt Stewart: https://tolkiengateway.net/w/index.php?curid=14232)

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (Mariner Books, 2004), 195, 198. Kindle.

[2] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 729, 915.

[3] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 330, 444, 540-541.

[4] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 119-120, 134, 141-142.

[5] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, ed. Christopher Tolkien (London: HarperCollins, 2013), 212-213.

[6] Tolkien, The Silmarillion, 1-12.

Awesome piece. Worth mentioning, while not Tolkien, it’s so fitting that the greatest soundtrack ever made is Howard Shore’s score for the Lord of the Rings movies

The Ainulindale is, in my opinion, the single most beautiful piece in all of Tolkien's writing. There is mystical theology in there to dwell on for a lifetime. I've written one short piece of my own on it, but it's so incredibly deep, I don't know I'll ever exhaust it. The implications it has for the music of the Christian liturgy are fascinating, especially given the idea that the Christian liturgy is a participation in the creative redemptive work of God where our music is united with His Word, culminating in the mystery of the Eucharist.